The classic dungeon exploration scenario involves searching amid scarcity.

The classic dungeon was once rich, but was also abandoned long ago. Since then, most of what was valuable has already been stolen by the looters and tomb-robbers of an earlier generation. What hasn't been taken away has mostly rotted or crumbled to dust. Invaders have moved in and trashed the place further.

There are treasures here, but they're all trapped, guarded by monsters, or hidden. Sometimes you get lucky, and there's a magic sword sitting on a plinth, just waiting for you to claim it.

All the rest of the time, there's a treasure chest in the middle of a room, but you just know that it's not what it looks like. It's empty, or there's a poison needle waiting to stab you when you try to open the lock, or there's a trap door right in front of it waiting to drop you into an alligator pit when you walk up, or else it's not really a treasure chest, it's just a monster that looks like one.

Or you see the monsters first, and you can only find their treasure after you kill them and start going through their stuff.

Or you're in a room that looks like it's empty, and you have to like, find the paving stone that sticks up slightly above the level of the rest of the floor because there's something under it. Or search all the furniture looking for false bottoms. Or tap all along the walls trying to find hollow spots that might indicate there's a secret door. Or break the furniture just in case, because maybe the jerk author who wrote your asshole GM's dungeon key said the treasure is hidden inside a hollowed-out table leg. Or maybe you're wasting your time because only 1-in-6 empty rooms have unguarded hidden treasure anyway.

Or finally you hit the jackpot and you're in the evil wizard's combination laboratory-library. This terror of the countryside, who amassed untold wealth from pillaging the countryside and demanding tribute owns ... one spellbook, a couple potions, a few scrolls. Maybe a talisman or a single magic ring.

And your characters, who are dirt poor, take everything they can find. They want everything that's not nailed down, then they want to pry up the nails and keep those too, because you never know when you might want to nail a door shut. (You never will. Those nails will still be on your character sheet, unused, at the end of the campaign, just like all the rubber bands your grandmother saved in a kitchen drawer - "just in case" - off every newspaper she ever received, and then never had any further use for, because growing up during the Great Depression convinced her that this was a wise and prudent use of space.)

Everything in the dungeon that can be taken is written down, and because it's too much of a pain to write very much of that sort of thing, there's not that much written, and so the dungeon is mostly empty.

But what if it was different?

What if, instead of poverty, there was plenty? What if instead of scarcity, there was abundance? What if your characters weren't poor, they were rich, and instead of taking everything, they only wanted to take the best things? What if the interior of the dungeon didn't resemble an empty cave or an abandoned warehouse, what if it was opulent, palatial? What if it wasn't abandoned, but living, and what if the people who lived their were your people, or at least were people whose good opinion you craved and respected?

What if, instead of playing a meth addict ripping the copper wires out of the walls of an abandoned trailerpark doublewide, you played a gentleman thief, plucking only the very finest, very choicest items from out of the museums and display halls of the inordinately wealthy and the exceptionally rich?

Or, I don't know, what if you were still poor, but that wizard you just killed had an actual library full of books, and only one of them was the spellbook? What if you're poor, but the world around you isn't, so if you bring an entire backpack full of books back to town, but none of them is the spellbook, then you'll end the adventure worse off than you started it, because books are cheap but an indoor place to sleep at night is not?

What if the problem wasn't finding anything in a place that, at first glance, appears to contain nothing, but rather finding the right thing in a place that appears to contain everything?

This is a follow-up, of sorts, to my thoughts about searching for treasure in dungeons where things might be landmark, hidden, or secret. It's a follow-up because I asked myself the question "what if everything was a landmark? what if the treasure was hidden-in-plain-sight? what if the treasure wasn't secret because you couldn't see it, but because you couldn't recognize it even though you were looking right at it?"

Running an abundant dungeon probably requires additional rethinking of the way the game designer writes up the dungeon, the way the gamemaster describes it, and the way the player approach it. But let's set all that aside for right now. For right now, let's focus on the question of how to mechanically adjudicate these searches.

When I talk about abundant dungeon spaces, I'm imagining rooms that are stuffed with objects. I guess this could just mean really well-appointed living spaces, but what I'm imagining are more like storage spaces that are filled with objects that look very similar but have very different monetary values. Imagine wading through a hallway filled with chairs. Imagining entering a bedroom where the floor around the bed is completely covered by teacups and saucers. Imagine finding a dressing room filled with masquerade costumes. Imagining opening a drawer stuffed with silverware or a cabinet overflowing with China. What happens if the players pick up the first one they find? What happens if they want to look close and pick out the best ones?

Landmark - In a room that's literally filled with treasure, let the players collect their treasure!

This advice contradicts what you might see in some other old-school sources, which I'll talk about in another post. OSR authors generally encourage you to make most of the apparent treasure in these places worthless. Find a library? All the books are moldy, rotten, and illegible. Find an armory? All the weapons are rusted and unusable. Etc.

I disagree! Let the players take home their treasure, and make it worth something!

Obviously, just picking up the first objects you find isn't the most effective way to find the most expensive treasure, but that doesn't mean what they find should actually be worthless. I would assign a nominal monetary value to each item, and let the accumulated value add up. Silverware is probably worth a coin each, collecting a drawer full is like finding a strongbox of silver pieces. Other objects might be more difficult because they're heavy or bulky or fragile or some combination of the above. Anything like that is probably worth 2, 5, or at most 10 coins.

Just picking up whatever you can find is a beginner's strategy, and players will learn to be more discerning once they realize there are ways to earn far more cash for their efforts. But un-directed accumulation can also be a stepping-stone to connoisseurship, by allowing characters to begin accidentally collecting matched sets.

Whenever the characters bring their treasure back to their hideout, you can check whether any of the individual items of the same type are part of a matched set. (Looking at the birthday paradox suggests that the chances of having at least 2 items in the same set should increase very rapidly the more you find, but that math seems really complicated to simulate at the table, so let's ignore it.)

Roll d20, and try to get lower than the number in your collection. Yes, that does mean if you have 20 or more items of the same type, then at least 2 are guaranteed to be part of the same matched set. Roll a dice determined by the set type, and that will tell you how many items are part of the same matching set. So for example, if you were collecting silverware, you would roll d4+1 to see how many pieces are part of the same matching place-setting. Other kinds of sets might require you to roll d6+1, d8+1, etc. Subtract that number out of your total collection, and roll the d20 again. You might have multiple different matched sets, so keep this up until you roll too high.

Items that belong to a matched set are much more valuable than unmatched items. So if a single piece of silverware is worth 1 sp, a set of two is worth 3 sp (2! = 1 + 2), a set of three is worth 6 sp (3! = 1 + 2 + 3), etc. If that scale-up somehow doesn't impress you, then try making each additional piece even more valuable, so two pieces are worth 4 sp (1! + 2! = 1 + 1 + 2), three pieces are worth 10 sp (1! + 2! + 3! = 1 + 1 + 2 + 1 + 2 + 3), etc. Either way, the point is that each additional matching piece substantially increases the value of the whole collection.

You now have the choice to sell your incomplete set for a decent price,

or you can try finding more pieces to make even more bank. Just like that, your players have a sandbox-like goal! This can help direct their exploration within the dungeon, and might even give them a reason to return to the room where they found the first part of their collection.

The next time you gather items of an existing type, roll under d20 for the new items to see if any belong to your current sets. If you get a match, roll d4-1 (or whichever dice is appropriate) to see how many are duplicates of existing pieces. If you get a 0, it's a new piece that fits into an existing collection. Congratulations! Roll again to see how many duplicates you found at the same time. After you've finished checking for matches to your existing sets, check again for your entire collection, which might now contain some new partial matching sets thanks to the additional pieces. (If your GM is feeling really generous, you can also see if any of your mini-sets belong to an even larger mega-set. Just check them in the same way, but treat each little set as an individual "piece" of the larger set. Perhaps some of your complete place-settings have the same pattern and belong to the same table-service, for example.)

Silverware is admittedly an unexciting type of item to collect, but you could apply this same logic to pieces of clothing making up uniforms or suits, chess or mahjong pieces, idols of gods in the same pantheon, china pieces in the same tea-set, or especially books in the same multi-volume series. Not every possible item needs the opportunity to be part of a matched set, but for key items you want your players to collect, this is a simple way to segue from simple smash-and-grab dungeoneering to goal-directed reconnaissance and investigation.

This idea is currently untested, but I think it should work in a gaming environment. From knowing a friend who collects rare books, I know that filling out a partial collection is massively more difficult than I've made it seem here. (It's the birthday paradox again. For the same reason it's easier than you'd expect to find the first match, it's harder than you'd expect to find the last unique element.) But I feel like performing virtually any task in a game ought to be easier and more fun than doing it in real life, particularly if that task is one the game itself is encouraging you to perform. We don't need an accurate simulation of real-world probability, we need a mechanic that allows us to adjudicate complex actions in a simple way.

Hidden - What if you're not just looking for any items, you're looking for items of particular value? In that case, you're not spending time picking up everything you can carry, you're spending time looking at what's available and picking out individual items somewhat selectively.

Foraging in the woods should probably work like this, for example. In a damp forest, you absolutely will find mushrooms or firewood or water if you spend a little time looking for it. In a library or bookstore, you will find interesting books. In a pantry storing tea or coffee or spices, you will find valuable varietals if you stroll about instead of swiping armfuls directly into your backpack.

The idea here is that in spaces of abundance, most of the items are relatively low-value, but higher-value items can be found if the characters spend time looking for them. Matching sets are a way to boost the sale-price of low-value items, but looking for hidden gems are worth finding all on their own. I would say that in the dungeon is your only chance to find a hidden gem. They will never turn up as part of a smash-and-grab operation.

Think of collecting wine bottles out of a wine cellar, for example. Most bottles will be worth whatever's the normal amount for wine in your game, although you can increase the value by collecting a complete case of matching vintages. However, a few bottles would be more expensive if sold, or might provide minor medicinal benefits to a character who drinks it as a ration.

Or think again of gathering books in a library. Most volumes are probably parts of some sort of series - maybe the complete works of some minor author, maybe encyclopedias, or textbooks organized by grade level, or annual reports from colleges or companies or churches, maybe historical chronicles, or all the editions of a particular magazine or newspaper bound together by year, maybe really boring stuff like a social register, or a listing of military members, or shipping manifests, or business ledgers. They might have research value or look good on your shelf, but they're only particularly valuable in a series. But there are also interesting individual books, which could have all kinds of game benefits. (I could write a whole blog post, and probably should, about all the ways you could use books in your game.)

The items you find this way should have an increased value, say 10 or 25 times the usual price of un-matched items of the same type. They should also, I think, have minor beneficial abilities. These should either be less impressive than full-on magical powers, or they should be the weakest magic available in your game.

Spending the time to find hidden gems is also a way to improve your existing collections. If you look carefully, you will find items that belong with one of your matched sets. You'll still need to roll to see if there's a unique piece or only duplicates, but you can skip the initial d20 roll for the match.

Secret - Finding something really valuable amid an ocean of near identicals requires a discerning eye, cultured taste, a shrewd sense for appraisal, and perhaps a bit of luck. There's always a chance of failure, but if you succeed, you'll have found something unique.

I mentioned before that I think the purpose of game mechanics is not to simulate reality but to allow us to make complex determinations quickly enough to use these decisions at the game table, and frankly, to put a thumb on the scale in favor of fun and interesting outcomes. So look, yes, in reality, the determining factor in these kinds of searches is whether or not a really valuable thing is actually there. Not every rummage sale has an original Shakespeare folio, not every thrift store has an undiscovered Picasso, no matter how hard you look. And if there is such a treasure present, then it shouldn't matter if you find it there in the store, or if you buy up the entire inventory in order to sift through it at home.

But since this is a game, and since the point of dungeoneering is that dungeons are storehouses of riches uncountable, let's sort of assume that there is a real treasure present in every abundant dungeon room, but you can only find it if you make an appropriate skill check and succeed your roll. (Look! I finally found a use for the appraisal skill besides pretending you don't know how to look up prices in the equipment section of your game rules!) You'll never find this treasure if you spend time but don't pass the skill test. You'll never find it if you grab up everything and take it back home. I would however stipulate that if you have some sort of procedure for conducting research, either by studying appropriate reference books, or collecting enough mundane examples, or both, you can also find these treasures by making sufficient research progress, rather than risking a skill check.

I would say that these treasured items should be worth 100 or 250 or 500 or 1000 times as much as their mundane counterparts. I would also say that they ought to be full-on magic items with powerful effects. This is the good stuff. It's not enough to grab the first thing you see, not enough to just spend time looking for it. If you manage to find one of these treasures, it had damn well better be worth it.

If you use your search for secrets to find an item for an existing collection, you will find a unique item that fits into an existing collection, in addition to the usual number of duplicates. (If your GM is really playing hardball, then this might be the ONLY way to find the last item that finishes off and fully completes a matched set. If so, just make sure that the choice to finish a collection has roughly the same financial pay-off as finding a unique treasure.)

So, now you have a plan for running an abundant dungeon, a plan that doesn't involve just giving the appearance of treasure while actually declaring almost everything worthless. And, you have a mini-game for your players to try collecting matching sets for extra cash, or to especially seek out the b-sides and rarities amid the masses.

My only final word on this is that even in a dungeon that includes abundance, not everything needs to be abundant. It's probably more interesting for your plays (and much easier for you!) if pick a few categories of treasures that feel thematically appropriate, and allow them to exist in abundance. You will need to do some extra preparation so you can describe the appearance of the things they're finding, give a formal or informal name to the matching sets, and assign special properties to the hidden or secret items.

I promised at least two follow-up posts in the process of writing this, one to look at other OSR authors's advice for managing abundance, and one to think about how to write abundance without having to enumerate your own private Doomsday Book in the process.

Friday, December 27, 2019

Thursday, December 19, 2019

Knitted Miscellany - Felted Food, Crochet Coral Reef, Mathekniticians, Programmable Yarn

How to Crochet a Coral Reef - and Why

Sarah Derouin

Scientific American

"The crocheted corals display hyperbolic geometry, a type of geometry that is neither planar nor spherical; Picture hyperbolic geometry as a sort of saddle shape with curves and dips. Nature loves hyperbolic geometry and you can see examples of it in the sea (sea slugs and corals) or in your salad bowl (curly kale leaves). As it turns out, crochet is a perfect medium for creating rippled, ruffled edges seen in corals."

This Los Angeles Grocery Store Has 31000 Items - and You Can't Eat Any of Them

Carlye Wisel

Smithsonian

"The potato chips, Butterfinger bars and ramen packets inside Sparrow Mart may look real, but they’re all handmade from felt. The combination art exhibit and supermarket, is stocked with an array of 31,000 produce, liquor, frozen and fresh food items, all of which are for sale. The entirety of Sparrow Mart’s functional equipment - grocery case, deep freezers, even the ATM - are covered in felt too; add branded shopping carts and grocery baskets to the mix and it’s the full experience."

See the Adorable New Grocery Store in Rockefeller Center Where Everything is Art

Sarah Cascone

Artnet News

"Delicatessen on 6th specializes in fresh produce, with organic kale, ripe avocados, and tidy bunches of spring onions displayed in rustic wooden crates. The deli counter with its cold cuts and sliced cheese is out, replaced by a butcher station featuring freshly ground beef and premium cuts of meat. All in felt. You’ll also find all manner of soft-sculpture seafood, including ruby red lobsters, shiny sardines, and oysters that you can actually shuck, removing the smiling bivalves from the shells. For the first time, Sparrow has created a cheese counter, a bakery, and a patisserie, recreating every aspect of a fancy food emporium."

Meet the Mathekniticians - and Their Amazing Woolly Maths Creations

Alex Bellos

Guardian

"Not only are the images in the afghans mathematical, but the way they are made also involves mathematical thinking. 'We enjoy the challenge of seeing an idea then working out how it can be made into an afghan in a way that would be easy enough for anyone else to recreate. It is like trying to solve a puzzle and refining it to give the best possible solution.' "

'Knitting is Coding' and Yarn is Programmable in this Physics Lab

Siobhan Roberts

New York Times

"The investigation is informed by the mathematical tradition of knot theory. A knot is a tangled circle - a circle embedded with crossings that cannot be untangled. (A circle with no crossings is an 'unknot.') The knitted stitch is a whole series of slipknots, one after the other. Rows and columns of slipknots form a lattice pattern so regular that it is analogous to crystal structure and crystalline materials."

"Knitted fabric is a metamaterial. A length of yarn is all but inelastic, but when configured in slipknots - in patterns of knits and purls - varying degrees of elasticity emerge. Just based on these two stitches, these two fundamental units, we can make a whole series of fabrics, and each of these fabrics has remarkably different elastic properties."

Monday, December 9, 2019

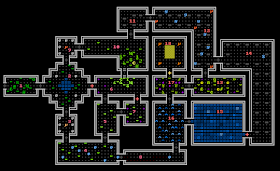

Roguelike Advice for Tabletop Games from @Play and Golden Krone Hotel

John Harris of the @Play blog and @Play column writes about "rougelike" videogames. Since I am somewhat interested in procedural generation in tabletop gaming, there are a few of his columns that I particularly like. There are also a couple contrarian pieces from Jeremiah Reed of Golden Krone Hotel, and some ASCII art I like from Uncaring Cosmos and Imminent Demon Engine, and some links at the end for resources for making ASCII and pixel art.

Purposes for Randomness in Game Design is about reasons to use procedural generation instead of "set" content in a videogame.

- to make multiple playthroughs of the same game interesting

- to offer a game some resistance against "spoilers"

- to challenge players' skills by asking them to deduce things about the gameworld

- to create emergent narratives that wouldn't arise any other way

- and to create emergent complexity by randomly combining basic elements

In tabletop gaming, I would add the reason that it allows the gamemaster to discover the world at the same time as the players. I would also add that one of the challenges of procedural generation at the tabletop is that proc gen makes it harder to offer players a meaningful, clue-filled environment where they can successfully deduce what's around each corner - so it's quite interesting to me that he lists that as a strength.

Eight Rules of Roguelike Design is kind of a manifesto for rougelike gaming. Most of these seem like good advice for any dungeon, and a few at the end are especially relevant for resource-management, exploration-style gaming. It's worth remembering that if you want your players to interact with the mysteries of the dungeon, they'll be more inclined to do so if those mysteries aren't usually harmful, and if even the harmful ones aren't instantly lethal.

Some of the advice about unidentified items initially struck me as being kind of narrow and genre-specific, until I remembered that item identification is a kind of mini-game inside Numenera and Mutant Crawl Classics, among others.

- no player character should be immediately killed by a single monster attack

- no player character should be immediately killed by testing an unidentified item

- magic items should require testing to identify, even for players with a lot of system knowledge

- each magic item type should have enough potential effects that testing it during combat is potentially beneficial but also potentially harmful

- magic items should have both benefits and penalties (or at least limitations) so that they present interesting choices

- because magic items have both upsides and downsides, no item should ever be completely useless

- exploring the dungeon should use up a resource so that players aren't able to explore indefinitely

- as you explore deeper into the dungeon, monsters should become more dangerous a little faster than player characters become stronger (so that magic items become more important over time)

Towards Building a Better Dungeon is all about the things tabletop games still do better than computer games. There are a number of experiences and mechanics that I've noticed work better for single players than they do for groups, or that work better when a computer is handling the numbers than when humans are, so it's nice to see someone from the other side praising what works better in our world.

It's also interesting to see which aspects of of D&D he admires. It's many of the same things you see praised on OSR blogs, for example. Although the staircase thing seems like it's an artifact of the way rougelike games randomly generate their maps - it seems so common-sensical to me that I struggled to even write the one sentence summary, but apparently it's an issue for them. There are other elements of old-school D&D that would be difficult to replicate, such as factions of monsters that want to recruit you into their internecine conflicts, but what he focuses on are mostly the elements that would enrich solo play.

- D&D has varied, interesting that are placed deliberately rather than randomly

- monsters in D&D come in different sizes, from small to large

- old-school D&D requires narrative searching to find secret doors

- on multi-level D&D maps, staircases are placed consistently in relation to one another

- despite its difficulty magic item identification is actually easier than in Gygaxian D&D (I suspect roguelike games also don't contain Gygax's, uh, rogue's gallery of look-alike monsters that exist solely to punish his players for adopting the very same playstyle he pushed on them. Also wait, someone is envious of this?!)

- you can't play roguelike games with your friends the way you can with D&D

Meanwhile over at Golden Krone Hotel, we get Things I Hate Sbout Rougelikes: Bog Standard Dungeons, which is, at least kind of, an argument against continuing to imitate D&D and Lord of the Rings in new games. My reading of this isn't that he's criticizing vanilla fantasy per say, but rather, that he's calling for more new games to employ a strong consistent theme that's not the same vanilla fantasy you see everywhere else. Of course, new games like Torchbearer, Dungeon World, and Forbidden Lands all developed large followings by selling "vanilla fantasy but with different rules" - so what's good artistic advice and what's sound marketing strategy might differ here.

There are three parts to his complaint:

- high fantasy is vanilla, and more importantly, it's overdone

- kitchen-sink bestiaries end up full of monsters that feel inappropriate or out of place

- a few "goofy" elements will quickly make an entire setting feel goofy (Which might be an argument in favor of going full-on gonzo. One joke monster just spoils the mood, dozens of joke monsters actually become the mood.)

I actually kept thinking about Jack Guignol's In Defense of Vanilla Fantasy while I was reading this. Because they initially seem like they're going to be in disagreement, but in some ways, I feel like they're two sides of the same argument. After all, when Jack says "they make vanilla so we don't have to", the argument here seems to be "they already HAVE made vanilla, so why do we keep making it too?" James David Nicoll has an ironic version of this plea, when he begs his readers to please, please "give the Tékumel and Gormenghast costumes a rest." Of course, Jack has a rejoinder to that, "vanilla might just be what people actually want" - like I said, there might be sound business reasons why so many game-makers keep making new vanilla games.

Even the Old School Renaissance has only one really weird megadungeon in its top five - Anomalous Subsurface Environment. Three of the others are high fantasy - Stonehell, Dwimmermount, and Castle of the Mad Archmage - and they all start out vanilla at the top and really only end up getting strange near their final levels. Barrowmaze is built out of basically vanilla components, but it has a narrow, consistent theme, and fills up its space by offering variations on that theme rather than a funhouse of new ideas. The biggest change as you go deeper is the slow shift from undead to demons.

Settings with a lot of novelty can run into the problem that "when everything is weird, nothing is weird." But the call here isn't for random weirdness, it's for a consistent theme that's simply a different theme than vanilla high fantasy. If it feels like you have a "kitchen-sink" full of monsters, if a handful of your monsters feel inappropriately "goofy," then the problem isn't that you have too much weirdness, it's that you don't have a consistently applied theme. Real weirdness is weird precisely because it stands out against its background - whatever that background happens to be. You can still have real weirdness even in a setting where everything is (initially) strange, but it will require using only a few stand-out elements (not a sinkful) and making them at least somewhat unique, not "goofy" and not just imported from another well-known genre.

So what games does he like? Unreal World, Cogmind, Hieroglyphika, Sproggiwood, Haque, Sil, Binding of Isaac, Nuclear Throne, Spelunky, and Caves of Qud. And presumably he likes his own game, Golden Krone Hotel.

In Item Design: Potions and Scrolls, we return to @Play to look at good design for these single-use items. Remember, half the criteria for good rougelike gaming are based on good magic items. He argues that magic items are so important for roguelike gaming because exploring the dungeons and fighting the monsters are not, by themselves, enjoyable enough to sustain interest in the game, only the items can do that over the long term.

In both rougelikes and old-school D&D, your character is adventuring for basically the same reason you're playing the game - for enjoyment. Your character explores dungeons and fights monsters to find money and cool stuff. Money (via XP) unlocks cool level-up abilities. Money lets you buy more cool stuff. Cool abilities and cool stuff in turn let you ... uh ... explore more dungeons and fight more monsters. So these things had better be enjoyable, because enjoying using them pretty much IS the entire purpose of the game - and if your game doesn't include any level-up abilities, then the cool stuff had better be especially cool!

He feels pretty strongly that single-use items should be unidentified until they're used, and even then, only if their effect is something that the characters could notice. So if you drank a potion of monster detection for example, and there were no monsters around to detect, the potion would seem to have no effect. There are also potions and scrolls that really do have no effect, just to keep you on your toes! While apparently one of the key pleasures of solo roguelike computer gaming, I think this kind of thing probably gets tedious very quickly in a tabletop game. (Apparently the only way to get Gygax to volunteer what your magic item did was to let a Rust Monster or Disenchanter destroy it. He was happy to tell you what you just lost! Otherwise you had to go into town, hope you could find a sage with the right expertise, and then hope the sage made their skill check. Tedious!)

There are a couple elements of roguelike potions and scrolls that don't show up much in D&D, and might be interesting to try including. The first is alchemy rules that reward you for mixing potions. Unless I'm misremembering, the "potion miscibility table" in D&D basically just says, "don't mix potions, or one of these twenty bad things will ruin your day!" The second element is scrolls that let you enchant your own weapons and armor. I've never heard of someone's campaign where players routinely turn their own mundane equipment into homemade magic items. It might happen occasionally, but it sounds like a common occurrence in roguelike games.

There is one element of D&D that he points out never makes it into the roguelikes - cursed items that are look-alikes for specific magic items. In a rougelike game, you're never going to successfully identify a Bowl of Commanding Water Elementals only to try using it and discover it was actually a Bowl of Watery Death, whereas basically all of D&D's cursed items function like that.

In Objects of Collection, he lays out a whole taxonomy of items that characters can find in the dungeon:

- basic one-use item, such as food rations

- one-use unidentified magic items, such as potions and scrolls

- wearable, always-on unidentified magic items, such as rings and amulets

- multi-use unidentified magic items, such as wands

- basic equipment, such as weapons and armor

- unidentified magic equipment

He notes a few other details about each type that are interesting to me, again primarily because they're a bit different from D&D. One-use unidentified items can also include special food rations that bestow some kind of benefit in addition to fending off hunger.

Wearable unidentified items typically have a very minor effect to compensate for the fact that they're always turned on - without the computer there to remember for you, these sound tailor-made to be forgotten about during play. They can also impose an additional cost in exhaustion and food consumption. A minor increase is too finicky to consider, but I wonder if needing to eat double or triple rations would be a meaningful cost in a resource-management game?

"Basic" equipment has a random component, too. Every sword or piece of armor you can find in a rougelike game will have a secret bonus, just like the simplest magic swords in D&D, which makes deducing each item's bonus anothertedious fun mini-game within roguelike play, but again, I wonder how well this would transfer to in-person play.

One thing I think is kind of neat is that unidentified magic equipment always has a predictable mundane use as well. So no matter which random magic power your magic snow boots have, they also always help walk through snow.

His final article in this series Rouge's Item ID In Too Much Yet Not Enough Detail isn't just a description of how magic item identification works in roguelike games, it's also a defense of the gameplay value of having unidentified magic items in the game to begin with. One really important thing to note, in case I haven't been clear enough about it yet, is that these unidentified items all come from a larger list, and you can find multiple copies of the same item during your game. So once you can identify an item, you don't just know "what was that thing I just used?" you also know "what will these other identical things do in the future?" The value he sees in having unidentified magic items would be considerably diminished in a game like Numenera, where theoretically every item is unique, rather than something you expect to find multiples of.

I get the sense that John Harris and other roguelike computer gamers would get along well with some portions of the OSR. He has a deep admiration for Gary Gygax and the original AD&D Dungeon Master's Guide, and he praises a number of design decisions in 5e.

So what does he thinks makes identifying unknown magic items a good part of roguelike play?

- it should be possible to use the item without identifying it first

- there should be some bad items so that using unknown items is a little risky

- sages and spells that identify an item without needing to use it should be rare

- the game needs to be difficult enough that players have to risk using unidentified items. they can't afford to wait until they achieve perfect safety to start unknown items out.

- items shouldn't be automatically identified when you use the. you only find out for sure what it is if it does something unambiguous under the present conditions.

- some item effects should be contingent on the character's status at the time of use

- bad items should have some positive use, even if it's just throwing them at monsters

- it should be possible to deduce what some items do without using them

- there should be more items in the game than can be found in one playthrough

For a contrary view, we once again return to Golden Crone Hotel for Things I Hate About Roguelikes: Identification, where Jeremiah Reed proposes a solution that's oddly reminiscent of his last one - to solve the problem by reducing its complexity. Previously, he argued we could "fix" funhouse dungeons by applying a theme to limit what kinds of monsters can appear. Here, he suggests that we can fix magic item identification by reducing the number of possible types that any particular unidentified item could be. I'll come back to that in a second.

His critique of roguelike identification is probably not that hard to guess, but let's look at it briefly anyway. He starts with a series of examples showing the many ways a player can die while using an unidentified magic item, either because the item was directly harmful, or because it provided no help in a dangerous situation.

- Outcomes like that are especially punishing on novice players. Experienced players should be rewarded for their accumulated system-knowledge, but it shouldn't be impossible for someone without that knowledge to play the game.

- It encourages item-hoarding (more on THIS in a second, too) which both makes the game more boring and makes it harder to survive.

- It makes using unidentified items feel like a trap, even though it's not supposed to be. (There's a similar problem in negadungeons, although there it feels like everything's deadly because truly everything IS deadly and will kill you if you interact with it.)

- And for all that, there are enough meta-game tricks that sufficiently system-knowledgeable players can accurately guess what most items are with in-game identifying them. Which seemingly defeats the purpose of making them unidentified in the first place.

So as a solution, he proposes that unidentified potions come in groups of three - each potion is recognizable enough that it could be one of three different things. As an example, he shows a character considering drinking a potion that might be a ration of honey, an antidote to poison, or teleportation in a bottle. The idea here is to encourage players to take more risks with their characters by limiting the scope of their choices. You still don't know exactly which effect you'll get, but it won't just be a dice roll on a d100 table - it'll be one of three things, and importantly, you'll know the worst thing that could happen when you make your choice.

I genuinely like this idea, and I feel like it could have other applications. You see a monster at the end of the hallway. It's a skeleton, and your cleric is certain its one of three possible undead creatures. Or you find a scroll in an unknown language. Even before you translate, your wizard thinks it could have one of three possible effects. Or you enter a room know that you've just stepped on a pressure plate. Before you lift your foot, your rogue tells you the three possible traps you might just have triggered. I particularly like the thought of applying this approach to Zonal anomalies.

There are only two difficulties with putting this idea into action in D&D. The first is that it would take a bit of preparation to add in this extra potential information into an adventure that didn't already include it. The second difficulty is that without a computer to do the hard work for you, it would really take some preparation to re-randomize these associations after each playthrough. Having DM aids that are essentially worksheets you fill out in advance (like the ones Signs in the Wilderness makes) would certainly help.

Finally, all this talk about single-use items got me thinking about Razbuten's video Consumable Items (And Why I Barely Use Them). After all this talk about identifying items, it's worth thinking about what makes you want to use them. The "barely use them" problem is definitely me walking around with a full complement of missiles that I never fire in Super Metroid, or accumulating dozens of Mushrooms and Tanuki Leaves in Mario 3. Razbuten divides single-use items into two categories - "reactive" items that restore hit points or eliminate status injuries (like poison or blindness), and "active" items that proactively affect the world. He argues that most players will use "reactive" items whenever they need to, but end up saving (and forgetting!) their "active" items.

One reason he thinks this happens is that players can often pretty easily win fights and beat the game without using any items. He notes that he uses more items on harder difficulty settings, where the extra boost is the only way he's able to win fights that he can simply hack and slash through at normal difficulty. I think this goes to @Play's earlier point that roguelike games ought to get harder faster than the hero character gets stronger, which will make equipment more important over the course of the game. Having a few monsters that are much stronger than the others can encourage you to use your items to win those fights in particular - although possibly at a cost of wanting to "save up" for those fights.

Making ALL equipment temporary might also encourage players to use single-use items more freely. Instead of using a permanent item to preserve your single-use items, you might be tempted to use up a single-use item to prolong the lifespan of some of your other equipment. Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild does this, as does the old SNES game Brandish. This could be a little hard to track in a game where a computer isn't counting your sword-strokes, but of course you can make the attack roll do the work for you. If even the best items break on a natural 1 (and less durable items break on a wider range) then nothing is permanent, and you need to keep finding new weapons and new armor throughout the game. (That one might be a hard sell for your players though. A bronze age or stone age setting could make it more palatable.)

Making new items easy to find is another suggestion for getting people to use them instead of hoarding them. There's no reason to try to save up your items if you can be pretty sure you'll keep finding more. Perhaps you could combine that with an encumbrance system that does't LET you build up a large supply, which is more or less what Numenera does - its single use items are plentiful and most characters can only carry 3 at a time early in the game, so you have a strong incentive to use them, and little reason to save them, even though each one is unique. You might also just have to accept that most players WON'T use "special" items under "ordinary" circumstances. The key to encouraging their use, then, would be to increase the number of "extraordinary" situations where item use becomes more likely.

Having non-combat puzzles to solve can encourage experimentation, which is a point that Joseph Manola has made before. It's also consistent with my own behavior in using the slightly-harder-to-replenish "boss power" weapons in Mega Man X. When faced with a problem that has no really obvious straightforward solution, I'm more likely to start experimenting with my equipment. Probably this is true of other players as well. Breath of the Wild includes areas that you can only reach by drinking certain potions to increase your abilities, and of course Super Metroid has its various lock-and-key puzzles where specific equipment items open up whole new areas on the map that are otherwise inaccessible. Puzzles and hard monsters, then, present a pair of difficult situations where players will "dig deep" to stay alive and overcome the challenge, and so they're both perfect times to use special items.

FINALLY finally, if looking at the ASCII and pixel art from earlier got you interested in making your own, here are a few links to free tools. When I posted about ASCII art once before, several people suggested resources to me, and I wanted to share them now. Each of these was recommended by at least one person who seemed to be in a position to know.

advASCIIdraw is a free program for drawing your own ASCII dungeon maps (and presumably anything else you'd like to draw using ASCII characters?)

Oryx Design Lab is not free, but they do sell packages of pixel-art images that you can use in your own games, including ones you plan to sell. Their prices are $25-$35 for an entire collection, and one of their collections is a rougelike tileset, which I believe is what Uncaring Cosmos used for their graphics.

Open Game Art is a repository for free, open-source, and Creative Commons pixel art. All of the art is free to download and free to use, although some artists may have licenses that only allow their art to be used in free products, while others will also allow their art to be re-used in something you're selling.

Lospec has a number of resources for making pixel art. They have a nifty list of artist-submitted color palettes, sorted by popularity, and with a number of search options. They have a free in-browser pixel art program, and a whole list of resources for for making pixel art, finding software, or locating communities of other pixel artists.

Playscii is another free program for making ASCII art. This one can make still images, animation, and can be used to make playable games.

|

| image by Uncaring Cosmos |

|

| image by Uncaring Cosmos |

Purposes for Randomness in Game Design is about reasons to use procedural generation instead of "set" content in a videogame.

- to make multiple playthroughs of the same game interesting

- to offer a game some resistance against "spoilers"

- to challenge players' skills by asking them to deduce things about the gameworld

- to create emergent narratives that wouldn't arise any other way

- and to create emergent complexity by randomly combining basic elements

In tabletop gaming, I would add the reason that it allows the gamemaster to discover the world at the same time as the players. I would also add that one of the challenges of procedural generation at the tabletop is that proc gen makes it harder to offer players a meaningful, clue-filled environment where they can successfully deduce what's around each corner - so it's quite interesting to me that he lists that as a strength.

Eight Rules of Roguelike Design is kind of a manifesto for rougelike gaming. Most of these seem like good advice for any dungeon, and a few at the end are especially relevant for resource-management, exploration-style gaming. It's worth remembering that if you want your players to interact with the mysteries of the dungeon, they'll be more inclined to do so if those mysteries aren't usually harmful, and if even the harmful ones aren't instantly lethal.

Some of the advice about unidentified items initially struck me as being kind of narrow and genre-specific, until I remembered that item identification is a kind of mini-game inside Numenera and Mutant Crawl Classics, among others.

- no player character should be immediately killed by a single monster attack

- no player character should be immediately killed by testing an unidentified item

- magic items should require testing to identify, even for players with a lot of system knowledge

- each magic item type should have enough potential effects that testing it during combat is potentially beneficial but also potentially harmful

- magic items should have both benefits and penalties (or at least limitations) so that they present interesting choices

- because magic items have both upsides and downsides, no item should ever be completely useless

- exploring the dungeon should use up a resource so that players aren't able to explore indefinitely

- as you explore deeper into the dungeon, monsters should become more dangerous a little faster than player characters become stronger (so that magic items become more important over time)

Towards Building a Better Dungeon is all about the things tabletop games still do better than computer games. There are a number of experiences and mechanics that I've noticed work better for single players than they do for groups, or that work better when a computer is handling the numbers than when humans are, so it's nice to see someone from the other side praising what works better in our world.

It's also interesting to see which aspects of of D&D he admires. It's many of the same things you see praised on OSR blogs, for example. Although the staircase thing seems like it's an artifact of the way rougelike games randomly generate their maps - it seems so common-sensical to me that I struggled to even write the one sentence summary, but apparently it's an issue for them. There are other elements of old-school D&D that would be difficult to replicate, such as factions of monsters that want to recruit you into their internecine conflicts, but what he focuses on are mostly the elements that would enrich solo play.

- D&D has varied, interesting that are placed deliberately rather than randomly

- monsters in D&D come in different sizes, from small to large

- old-school D&D requires narrative searching to find secret doors

- on multi-level D&D maps, staircases are placed consistently in relation to one another

- despite its difficulty magic item identification is actually easier than in Gygaxian D&D (I suspect roguelike games also don't contain Gygax's, uh, rogue's gallery of look-alike monsters that exist solely to punish his players for adopting the very same playstyle he pushed on them. Also wait, someone is envious of this?!)

- you can't play roguelike games with your friends the way you can with D&D

Meanwhile over at Golden Krone Hotel, we get Things I Hate Sbout Rougelikes: Bog Standard Dungeons, which is, at least kind of, an argument against continuing to imitate D&D and Lord of the Rings in new games. My reading of this isn't that he's criticizing vanilla fantasy per say, but rather, that he's calling for more new games to employ a strong consistent theme that's not the same vanilla fantasy you see everywhere else. Of course, new games like Torchbearer, Dungeon World, and Forbidden Lands all developed large followings by selling "vanilla fantasy but with different rules" - so what's good artistic advice and what's sound marketing strategy might differ here.

There are three parts to his complaint:

- high fantasy is vanilla, and more importantly, it's overdone

- kitchen-sink bestiaries end up full of monsters that feel inappropriate or out of place

- a few "goofy" elements will quickly make an entire setting feel goofy (Which might be an argument in favor of going full-on gonzo. One joke monster just spoils the mood, dozens of joke monsters actually become the mood.)

I actually kept thinking about Jack Guignol's In Defense of Vanilla Fantasy while I was reading this. Because they initially seem like they're going to be in disagreement, but in some ways, I feel like they're two sides of the same argument. After all, when Jack says "they make vanilla so we don't have to", the argument here seems to be "they already HAVE made vanilla, so why do we keep making it too?" James David Nicoll has an ironic version of this plea, when he begs his readers to please, please "give the Tékumel and Gormenghast costumes a rest." Of course, Jack has a rejoinder to that, "vanilla might just be what people actually want" - like I said, there might be sound business reasons why so many game-makers keep making new vanilla games.

Even the Old School Renaissance has only one really weird megadungeon in its top five - Anomalous Subsurface Environment. Three of the others are high fantasy - Stonehell, Dwimmermount, and Castle of the Mad Archmage - and they all start out vanilla at the top and really only end up getting strange near their final levels. Barrowmaze is built out of basically vanilla components, but it has a narrow, consistent theme, and fills up its space by offering variations on that theme rather than a funhouse of new ideas. The biggest change as you go deeper is the slow shift from undead to demons.

Settings with a lot of novelty can run into the problem that "when everything is weird, nothing is weird." But the call here isn't for random weirdness, it's for a consistent theme that's simply a different theme than vanilla high fantasy. If it feels like you have a "kitchen-sink" full of monsters, if a handful of your monsters feel inappropriately "goofy," then the problem isn't that you have too much weirdness, it's that you don't have a consistently applied theme. Real weirdness is weird precisely because it stands out against its background - whatever that background happens to be. You can still have real weirdness even in a setting where everything is (initially) strange, but it will require using only a few stand-out elements (not a sinkful) and making them at least somewhat unique, not "goofy" and not just imported from another well-known genre.

So what games does he like? Unreal World, Cogmind, Hieroglyphika, Sproggiwood, Haque, Sil, Binding of Isaac, Nuclear Throne, Spelunky, and Caves of Qud. And presumably he likes his own game, Golden Krone Hotel.

|

| image by Imminent Demon Engine |

|

| image by Imminent Demon Engine |

In Item Design: Potions and Scrolls, we return to @Play to look at good design for these single-use items. Remember, half the criteria for good rougelike gaming are based on good magic items. He argues that magic items are so important for roguelike gaming because exploring the dungeons and fighting the monsters are not, by themselves, enjoyable enough to sustain interest in the game, only the items can do that over the long term.

In both rougelikes and old-school D&D, your character is adventuring for basically the same reason you're playing the game - for enjoyment. Your character explores dungeons and fights monsters to find money and cool stuff. Money (via XP) unlocks cool level-up abilities. Money lets you buy more cool stuff. Cool abilities and cool stuff in turn let you ... uh ... explore more dungeons and fight more monsters. So these things had better be enjoyable, because enjoying using them pretty much IS the entire purpose of the game - and if your game doesn't include any level-up abilities, then the cool stuff had better be especially cool!

He feels pretty strongly that single-use items should be unidentified until they're used, and even then, only if their effect is something that the characters could notice. So if you drank a potion of monster detection for example, and there were no monsters around to detect, the potion would seem to have no effect. There are also potions and scrolls that really do have no effect, just to keep you on your toes! While apparently one of the key pleasures of solo roguelike computer gaming, I think this kind of thing probably gets tedious very quickly in a tabletop game. (Apparently the only way to get Gygax to volunteer what your magic item did was to let a Rust Monster or Disenchanter destroy it. He was happy to tell you what you just lost! Otherwise you had to go into town, hope you could find a sage with the right expertise, and then hope the sage made their skill check. Tedious!)

There are a couple elements of roguelike potions and scrolls that don't show up much in D&D, and might be interesting to try including. The first is alchemy rules that reward you for mixing potions. Unless I'm misremembering, the "potion miscibility table" in D&D basically just says, "don't mix potions, or one of these twenty bad things will ruin your day!" The second element is scrolls that let you enchant your own weapons and armor. I've never heard of someone's campaign where players routinely turn their own mundane equipment into homemade magic items. It might happen occasionally, but it sounds like a common occurrence in roguelike games.

There is one element of D&D that he points out never makes it into the roguelikes - cursed items that are look-alikes for specific magic items. In a rougelike game, you're never going to successfully identify a Bowl of Commanding Water Elementals only to try using it and discover it was actually a Bowl of Watery Death, whereas basically all of D&D's cursed items function like that.

In Objects of Collection, he lays out a whole taxonomy of items that characters can find in the dungeon:

- basic one-use item, such as food rations

- one-use unidentified magic items, such as potions and scrolls

- wearable, always-on unidentified magic items, such as rings and amulets

- multi-use unidentified magic items, such as wands

- basic equipment, such as weapons and armor

- unidentified magic equipment

He notes a few other details about each type that are interesting to me, again primarily because they're a bit different from D&D. One-use unidentified items can also include special food rations that bestow some kind of benefit in addition to fending off hunger.

Wearable unidentified items typically have a very minor effect to compensate for the fact that they're always turned on - without the computer there to remember for you, these sound tailor-made to be forgotten about during play. They can also impose an additional cost in exhaustion and food consumption. A minor increase is too finicky to consider, but I wonder if needing to eat double or triple rations would be a meaningful cost in a resource-management game?

"Basic" equipment has a random component, too. Every sword or piece of armor you can find in a rougelike game will have a secret bonus, just like the simplest magic swords in D&D, which makes deducing each item's bonus another

One thing I think is kind of neat is that unidentified magic equipment always has a predictable mundane use as well. So no matter which random magic power your magic snow boots have, they also always help walk through snow.

His final article in this series Rouge's Item ID In Too Much Yet Not Enough Detail isn't just a description of how magic item identification works in roguelike games, it's also a defense of the gameplay value of having unidentified magic items in the game to begin with. One really important thing to note, in case I haven't been clear enough about it yet, is that these unidentified items all come from a larger list, and you can find multiple copies of the same item during your game. So once you can identify an item, you don't just know "what was that thing I just used?" you also know "what will these other identical things do in the future?" The value he sees in having unidentified magic items would be considerably diminished in a game like Numenera, where theoretically every item is unique, rather than something you expect to find multiples of.

I get the sense that John Harris and other roguelike computer gamers would get along well with some portions of the OSR. He has a deep admiration for Gary Gygax and the original AD&D Dungeon Master's Guide, and he praises a number of design decisions in 5e.

So what does he thinks makes identifying unknown magic items a good part of roguelike play?

- it should be possible to use the item without identifying it first

- there should be some bad items so that using unknown items is a little risky

- sages and spells that identify an item without needing to use it should be rare

- the game needs to be difficult enough that players have to risk using unidentified items. they can't afford to wait until they achieve perfect safety to start unknown items out.

- items shouldn't be automatically identified when you use the. you only find out for sure what it is if it does something unambiguous under the present conditions.

- some item effects should be contingent on the character's status at the time of use

- bad items should have some positive use, even if it's just throwing them at monsters

- it should be possible to deduce what some items do without using them

- there should be more items in the game than can be found in one playthrough

For a contrary view, we once again return to Golden Crone Hotel for Things I Hate About Roguelikes: Identification, where Jeremiah Reed proposes a solution that's oddly reminiscent of his last one - to solve the problem by reducing its complexity. Previously, he argued we could "fix" funhouse dungeons by applying a theme to limit what kinds of monsters can appear. Here, he suggests that we can fix magic item identification by reducing the number of possible types that any particular unidentified item could be. I'll come back to that in a second.

His critique of roguelike identification is probably not that hard to guess, but let's look at it briefly anyway. He starts with a series of examples showing the many ways a player can die while using an unidentified magic item, either because the item was directly harmful, or because it provided no help in a dangerous situation.

- Outcomes like that are especially punishing on novice players. Experienced players should be rewarded for their accumulated system-knowledge, but it shouldn't be impossible for someone without that knowledge to play the game.

- It encourages item-hoarding (more on THIS in a second, too) which both makes the game more boring and makes it harder to survive.

- It makes using unidentified items feel like a trap, even though it's not supposed to be. (There's a similar problem in negadungeons, although there it feels like everything's deadly because truly everything IS deadly and will kill you if you interact with it.)

- And for all that, there are enough meta-game tricks that sufficiently system-knowledgeable players can accurately guess what most items are with in-game identifying them. Which seemingly defeats the purpose of making them unidentified in the first place.

So as a solution, he proposes that unidentified potions come in groups of three - each potion is recognizable enough that it could be one of three different things. As an example, he shows a character considering drinking a potion that might be a ration of honey, an antidote to poison, or teleportation in a bottle. The idea here is to encourage players to take more risks with their characters by limiting the scope of their choices. You still don't know exactly which effect you'll get, but it won't just be a dice roll on a d100 table - it'll be one of three things, and importantly, you'll know the worst thing that could happen when you make your choice.

I genuinely like this idea, and I feel like it could have other applications. You see a monster at the end of the hallway. It's a skeleton, and your cleric is certain its one of three possible undead creatures. Or you find a scroll in an unknown language. Even before you translate, your wizard thinks it could have one of three possible effects. Or you enter a room know that you've just stepped on a pressure plate. Before you lift your foot, your rogue tells you the three possible traps you might just have triggered. I particularly like the thought of applying this approach to Zonal anomalies.

There are only two difficulties with putting this idea into action in D&D. The first is that it would take a bit of preparation to add in this extra potential information into an adventure that didn't already include it. The second difficulty is that without a computer to do the hard work for you, it would really take some preparation to re-randomize these associations after each playthrough. Having DM aids that are essentially worksheets you fill out in advance (like the ones Signs in the Wilderness makes) would certainly help.

Finally, all this talk about single-use items got me thinking about Razbuten's video Consumable Items (And Why I Barely Use Them). After all this talk about identifying items, it's worth thinking about what makes you want to use them. The "barely use them" problem is definitely me walking around with a full complement of missiles that I never fire in Super Metroid, or accumulating dozens of Mushrooms and Tanuki Leaves in Mario 3. Razbuten divides single-use items into two categories - "reactive" items that restore hit points or eliminate status injuries (like poison or blindness), and "active" items that proactively affect the world. He argues that most players will use "reactive" items whenever they need to, but end up saving (and forgetting!) their "active" items.

One reason he thinks this happens is that players can often pretty easily win fights and beat the game without using any items. He notes that he uses more items on harder difficulty settings, where the extra boost is the only way he's able to win fights that he can simply hack and slash through at normal difficulty. I think this goes to @Play's earlier point that roguelike games ought to get harder faster than the hero character gets stronger, which will make equipment more important over the course of the game. Having a few monsters that are much stronger than the others can encourage you to use your items to win those fights in particular - although possibly at a cost of wanting to "save up" for those fights.

Making ALL equipment temporary might also encourage players to use single-use items more freely. Instead of using a permanent item to preserve your single-use items, you might be tempted to use up a single-use item to prolong the lifespan of some of your other equipment. Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild does this, as does the old SNES game Brandish. This could be a little hard to track in a game where a computer isn't counting your sword-strokes, but of course you can make the attack roll do the work for you. If even the best items break on a natural 1 (and less durable items break on a wider range) then nothing is permanent, and you need to keep finding new weapons and new armor throughout the game. (That one might be a hard sell for your players though. A bronze age or stone age setting could make it more palatable.)

Making new items easy to find is another suggestion for getting people to use them instead of hoarding them. There's no reason to try to save up your items if you can be pretty sure you'll keep finding more. Perhaps you could combine that with an encumbrance system that does't LET you build up a large supply, which is more or less what Numenera does - its single use items are plentiful and most characters can only carry 3 at a time early in the game, so you have a strong incentive to use them, and little reason to save them, even though each one is unique. You might also just have to accept that most players WON'T use "special" items under "ordinary" circumstances. The key to encouraging their use, then, would be to increase the number of "extraordinary" situations where item use becomes more likely.

Having non-combat puzzles to solve can encourage experimentation, which is a point that Joseph Manola has made before. It's also consistent with my own behavior in using the slightly-harder-to-replenish "boss power" weapons in Mega Man X. When faced with a problem that has no really obvious straightforward solution, I'm more likely to start experimenting with my equipment. Probably this is true of other players as well. Breath of the Wild includes areas that you can only reach by drinking certain potions to increase your abilities, and of course Super Metroid has its various lock-and-key puzzles where specific equipment items open up whole new areas on the map that are otherwise inaccessible. Puzzles and hard monsters, then, present a pair of difficult situations where players will "dig deep" to stay alive and overcome the challenge, and so they're both perfect times to use special items.

FINALLY finally, if looking at the ASCII and pixel art from earlier got you interested in making your own, here are a few links to free tools. When I posted about ASCII art once before, several people suggested resources to me, and I wanted to share them now. Each of these was recommended by at least one person who seemed to be in a position to know.

advASCIIdraw is a free program for drawing your own ASCII dungeon maps (and presumably anything else you'd like to draw using ASCII characters?)

Oryx Design Lab is not free, but they do sell packages of pixel-art images that you can use in your own games, including ones you plan to sell. Their prices are $25-$35 for an entire collection, and one of their collections is a rougelike tileset, which I believe is what Uncaring Cosmos used for their graphics.

Open Game Art is a repository for free, open-source, and Creative Commons pixel art. All of the art is free to download and free to use, although some artists may have licenses that only allow their art to be used in free products, while others will also allow their art to be re-used in something you're selling.

Lospec has a number of resources for making pixel art. They have a nifty list of artist-submitted color palettes, sorted by popularity, and with a number of search options. They have a free in-browser pixel art program, and a whole list of resources for for making pixel art, finding software, or locating communities of other pixel artists.

Playscii is another free program for making ASCII art. This one can make still images, animation, and can be used to make playable games.